Every Christmas Eve, Craig Joiner goes into his study, opens a drawer and plucks out two enormous black socks. This drawer contains all the keepsakes and trappings of a playing career that featured 25 Scotland caps and took him across the globe. He ran around the fields of Buenos Aires and Paris, Rustenburg and Dunedin, Brisbane and Treviso, with a thistle on his breast. He was part of Premiership title-winning squads and Heineken Cup challenges with Leicester Tigers. He helped Edinburgh to an improbable European quarter-final in 2004. He was richly admired for his speed and finishing.

All told, a fine haul of memories. These socks, though, stretched with use and fraying with the passage of time, hold special resonance.

In 1995, as a baby-faced 21-year-old, Joiner pitted himself against burgeoning greatness. Neither before nor since has the game seen anything like Jonah Lomu. The ultimate icon, the superstar of superstars.

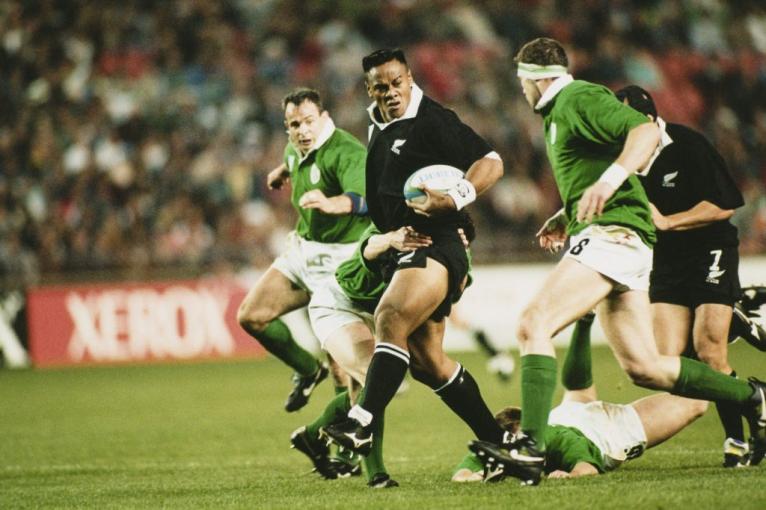

This was the World Cup quarter-final. Loftus Versfeld, Pretoria. Scotland versus New Zealand. Joiner versus Jonah. Joiner received the customary Lomu treatment that afternoon, which invariably ended with opponents eating turf and Lomu gobbling up tries. Twenty-eight years on, the juggernaut’s kit still plays a treasured role in the Joiner clan’s festive routine.

“Our two daughters’ stockings at Christmas time are Jonah’s socks,” he chuckles. “They have always been. The big fella’s socks are in front of the fireplace every year. They come out, have a few pressies stuffed in them, then get rolled up and shoved back in the rugby memorabilia drawer.

“Jonah didn’t swap jerseys back in those days; we swapped shorts and socks. I gifted the shorts to the Wooden Spoon charity which raised something like £3,000. They were in a bag in my attic and with the sad passing of Jonah, I thought, crikey, what should I do with these? My daughters said I should try and raise some money.”

Nobody outside New Zealand knew much about Lomu in 1995. He was only 19, after all. There were no online streams, no NPC matches beamed across the world on satellite television. No real inkling to those plotting a course for the World Cup that the mightiest tsunami was about to come crashing across their bows.

Lomu stood 6ft 5ins tall and weighed 120kgs. He was bigger than most locks and faster than any rival wing. He wreaked sheer destruction yet ran with such nimble grace, like a buffalo dressed in ballet pumps. He scored 37 tries in 63 Tests. Were it not for the chronic kidney condition that contributed to his desperate passing in 2015, those tallies would be even more jaw-dropping.

Richard Wallace got his introduction to Lomu courtesy of a journalist in the Sunnyside Hotel in Johannesburg, where he was preparing to play New Zealand in the opening pool match.

He could see the blood drain from my face. I thought, oh my god, what am I up against?

“Richard, how are you settling in? You’re up against Lomu – what do you think?” asked the reporter.

Wallace, a right wing, gave a noncommittal response about the typically abundant virtues of All Black widemen.

“He’s pretty big,” the journalist said.

“What do you mean?” Wallace replied.

“Well, he’s 6ft 5ins.”

“I’ve played against tall guys before”.

“And he does the 100m in 10.4 seconds.”

“I’ve played against Nigel Walker; if you get your angles right against faster guys you can do fairly well. That’s not so bad.”

“He’s 19-and-a-half stone.”

“He could see the blood drain from my face,” Wallace laughs. “I said something ridiculous like, ‘the bigger they are, the harder they fall’. I thought, oh my god, what am I up against here?”

If Wallace’s first brush with Lomu was jolting, his second was a proper head-wrecker. Literally. Deep inside his own 22, Ireland scrum-half Michael Bradley rather helpfully fly-hacked a loose ball straight into the giant’s arms. Lomu set off for the try line, on a fearsome collision course with Wallace. The Irishman was a sturdy customer, but as Lomu dropped his shoulder, and Wallace stuck his head in the spokes, he was left spreadeagled on the deck like a spent boxer.

“Not exactly your ideal first encounter with Jonah. I decided I’d go in low, let him run over me and take him as he went. That wasn’t such a good idea. He stepped around me and just put me on the floor and was gone. It was bloody embarrassing. I was his first major victim but he went on to take quite a few more.”

Ireland lost 43-19. Lomu scored two tries and eliminated half the emerald ranks before teeing up Josh Kronfeld for another. Kronfeld, the ultimate scavenger, scooped a barrowload of tries simply by tracking Lomu’s scything runs like a bloodhound.

“I didn’t have to do much one-on-one defending but my God, he made our lives a living hell in that game,” Wallace goes on. “He was the difference. If you took him out of the equation, it would have been much tighter.”

The Welsh were next. Between Gareth Thomas and Ieuan Evans, they did a reasonable job of keeping Lomu quiet. All things being relative, of course. He still made 74m from his six charges, scuttled five defenders and set up a try before suffering a minor injury in the final minutes that sent him hirpling to the sideline.

Laurie Mains, the All Black coach, allowed his game-breaker to rest as a rotated New Zealand savaged Japan mercilessly, the 145-17 shellacking sealing top spot in the pool.

Scotland – and Joiner – stood between them and a semi-final. The Scots were a team of sound pedigree. They had survivors from their 1990 Grand Slam and talent emerging apace. They had beaten everyone but England in the Five Nations, including a remarkable sacking of the Parc des Princes. They were led by the genius white lion, Jim Telfer. They had Gavin Hastings, one of the most immovable and dependable full-backs of any era, as their last line of defence should Lomu splinter the infantry. His brother Scott was a tough-tackling outside centre. Joiner preferred to use speed.

Nobody ever stopped him dead. You were left scratching your head.

Except, where Lomu was concerned, speed was redundant. In the early throes, New Zealand shipped the ball to Lomu and Lomu seared beyond Joiner like a passing freight train.

“There was nobody else like Jonah,” the Scot says. “You think you know, but it’s not until you’re really in the thick of it that you realise. I was pretty quick, I’d been a Scottish schoolboys sprinter and I was fairly confident if I gave most people the outside, I could reel them in.

“I’d seen him absolutely run over the top of people and I didn’t want that to happen, so I gave him more than enough space on the outside so I wasn’t going to be embarrassed getting trampled, and it turns out he was as fast as everyone said. I just couldn’t get close to him.

“I’m almost certain if I’d stood three or four metres further out, he’d have come straight at me. In hindsight that might have been the thing to do. But one person slowing him down didn’t seem to be enough. Nobody ever stopped him dead. You were left scratching your head.”

Joiner got a sliver of vengeance, scuttling by Lomu on a dart of his own, but the Scottish effort was futile. They lost 48-30; Lomu laid waste. The first try of his wince-inducing seven in six career Tests against Scotland.

Having seen the atomisation of Ireland and Wales, didn’t Telfer and his charges have some sort of plan?

“You weren’t even in the mindset of having a plan,” Joiner says. “In 1995, we’d quite comfortably beaten Ireland and Wales. We thought, New Zealand might do that to Ireland and Wales but they won’t do that to us. It was about individual responsibility. And I’m not the only person who came unstuck.”

This was the beauty of time. Without today’s analytical resources, almost no-one knew the size and the scale and the sheer force of the behemoth in their midst – until it was too late.

England did not believe such a fate would befall them either. They had reached the World Cup final in 1991 and avenged their showpiece loss to Australia in the 1995 last eight. Their team was founded on uncompromising forward crunch, the unerring boot of Rob Andrew, and the silken excellence of Jeremy Guscott and Will Carling in midfield. That blueprint had propelled them past Scotland to the Grand Slam months earlier.

Lomu did not so much stymie the blueprint as seize, shred and devour it, all inside 80 of the most famous rugby minutes of all time. Lomu, mouth agape, nostrils flaring, went off like a bomb. A detonation that sent shock waves reverberating around the sport. The legendary stampeding of poor Mike Catt. The obliteration of England’s previously formidable defence. The whirling of Tony Underwood by the collar like a cowboy wielding a lasso. It remains one of the tournament’s enduring images, buttressing Lomu’s irrepressible four-try performance.

I don’t even know whether I did wink, it was more of a nod of the head. I’m not going to be whispering sweet nothings to him.

“We’d won a championship on the back of strong pack, beaten New Zealand, Lomu-less but with Inga Tuigamala, in 1993,” Underwood says. “We’d beaten the world champions in the quarter-final so we had a game that was dominant. If it was about negating Jonah, hopefully our game plan was going to do that by dominating up front. And if it was about negating Jonah, you wouldn’t have picked me. It wasn’t arrogance, it was just, we’re going to play to our strengths.”

The ballad of Underwood and Lomu has had more topspin applied to it than a Wimbledon championship over the years. The story goes, Underwood winked at Lomu as New Zealand’s haka reached its climax; Lomu’s ire had been stoked by egregious media and curated messages from the All Blacks staff about things Underwood had allegedly said.

“Anyone who knows me knows I’m not like a boxer before a match,” says the Englishman, 28 years later. “I respected and loved the haka. I don’t even know whether I did wink, it was more of a nod of the head.

“I’m not going to be whispering sweet nothings to him. It was a nod of acknowledgement of, ‘thank you very much, I accept the challenge, and get on with the game’, as I always had done against the haka. That was all that was. A lot of that is just interpretation.

“I wasn’t privy to the week they had leading up to the game but I think he articulated they’d been feeding him with all sorts of snippets from the press of people taking things I said and twisting them, ‘he hadn’t faced someone like me before’, all this stuff, feeding him a heady cocktail of headlines, and he was in a bit of a frenzy for the game. Anything I did in that game would probably have been interpreted the same way.”

Underwood was fleet and deadly in attack but he gave up some eight inches and 35 kilograms in mass. Lomu made devastating use of the physics. That, perhaps, was to be expected. But the speed? Underwood, a flying machine in his pomp, couldn’t get near his hulking foe.

“I didn’t have that many opportunities to run at him but when I did he collared me and grabbed me by the neck, which would probably have got him sent off these days. On the one opportunity to have a one-on-one with him, he matched me. For such a big man, the bulk of the guy, to have that pace – that was the freakish thing.

“When I was attempting to tackle him, every time he got the ball it was in space, my defensive technique was not good enough, and I didn’t have the footwork to be closer to him. It wasn’t my game. My game wasn’t about defence. It was built on speed, finishing and creating opportunities.”

In a Durban hotel, Mark Andrews and Joel Stransky watched this one-man evisceration of the English powerhouse and, internally, allowed themselves a little groan. Kitch Christie, the late Springbok coach, sat with them. If he groaned, the Springbok boys didn’t hear it. Christie recorded the match on his VHS player. When Andrews and Stransky wandered off to play pool, the coach spooled his tape back to the start and watched the whole thing again. At full-time, he rewound the tape once more and watched it a third time. “We can beat them,” he said. Then he got up and left the room.

It sounded like a great plan until I realised he was coming back towards me.

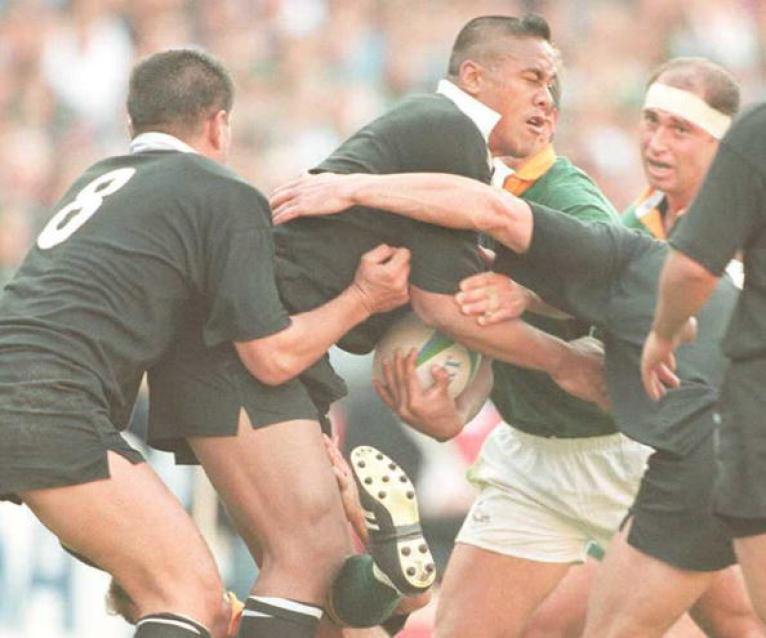

“Kitch called in the senior players on Monday,” Stransky recalls. “He told us, ‘to beat New Zealand we have got to stop Lomu’. Our defensive plan of rushing and shifting was not going to work, we could have put the biggest guy in the team out wide and he was going to beat them.

“Jonah comes in to the midfield, he comes behind the fly-half, he comes in for tip passes. Mark Andrews was playing at number eight, we discussed his role and the channel he would help defend. But most importantly, we said, ‘let’s stand wider and push him into the traffic – there’s safety in numbers!’

“We tried to use numbers to blunt the attack, slow him down and stop him, and just stop the All Blacks momentum. I always joke about it: it sounded like a great plan until I realised he was coming back towards me!”

Andre Joubert was another of Christie’s established cohort, a full-back of supreme class and guile. But if Lomu did penetrate the green and gold battalion, Joubert had a problem.

“I broke my hand in the quarter-final against Samoa so I couldn’t use both my hands to try and stop him. When he broke the line, you couldn’t stop him. You couldn’t allow a guy of 120kgs to build momentum. Then you are in trouble.

“Once you stopped him quickly, the All Blacks didn’t know what to do. Their whole game plan was around Lomu. That’s how we neutralised them – we stopped Lomu very quickly.

“We knew our best line of defence was our tackling. Hardly any team scored tries against us. We built our game plan around that. Our plan was to stop Lomu right away, or kick the ball behind him because he was slow in turning. We had to be secure on our kicking – don’t give him any space because then he can demolish anything and everything. He was definitely a kingpin to nail down.”

The infamous bout of food poisoning which decimated the All Blacks camp did not help Lomu’s cause. But wherever he thundered on that sun-baked Ellis Park paddock, a gang of ravenous Springboks followed. Japie Mulder clattered him into touch when he slipped through early on. Joost van der Westhuizen made a magnificent low tackle. Andrews and Ruben Kruger hauled the brute to ground.

“As great as he was, as massive as he was on the day, we managed to stop that threat,” Stransky says. “That buoyed us enormously. It inspired us, every time someone made a tackle on him it was a real uplifting moment for us. It became a self-fulfilling model for us to go and win the final.”

Then there was James Small. The epitome of the snarling, ebullient, emotionally charged Springbok. Small was troubled at times, misunderstood and probably mishandled too, but held in exceptionally high regard as an athlete. He puffed out his chest, summoned his courage and waged war on the huge black demon. It was David and Goliath stuff.

“James was a difficult character, with all respect to him, and he’d be the first to admit it,” says Stransky, who shared a room with Small on many of their international forays. “He was sensational with children, loved children, but with adults, not so much.

If there was one guy who was going to put his heart and soul on his sleeve and say, ‘you ain’t coming past me’, that was James.

“Life for James had had its ups and downs and that helped define who he was. As a winger went, he was quite bulky, strong, defiant, muscular. Nothing compared to Jonah – probably 20kgs lighter – but if there was one guy who was going to put his heart and soul on his sleeve and say, ‘you ain’t coming past me’, that was James. He had the attributes to back it up.

“It wasn’t conventional, he didn’t try and tackle Jonah around his thighs or his ankles or his knees, he went high, he scragged, got him by the jersey or the collar. He did it differently, but he did it. He was like a streetfighter. He had that nuggety approach. All guts and heart and undefeatable. Of all the people you want to play against an iconic player like Jonah, James is who I would want on my side.”

Tragically, like so many heroes in this game of games, Small is no longer here to tell his tale. Just as we lost Chester Williams and Joost van der Westhuizen and Ruben Kruger and Jonah Lomu himself, Small passed away much, far too young. A heart attack claimed his life in July 2019.

Thanks to Stransky’s extra-time drop-goal, the try-less showpiece was clinched by the Springboks. They were the first nation to truly nullify Lomu. And they remain the only country to do so consistently, for the great man never touched down in twelve matches against South Africa.

The 1995 World Cup belonged to Boks. And, for all its significance to a nation reborn after the horrors of apartheid, thank heavens it did. The image of Nelson Mandela and Francois Pienaar clutching the trophy is the most important and influential in rugby history.

But even as they revelled in the glory, Stranksy says South Africa knew they had witnessed the birth of a phenomenon.

“You don’t change your whole strategy for one guy unless that one guy is unbelievably special. We knew he was a sensation. If one player has that impact on a team, in a World Cup final, then he’s iconic.”

In later life, many seasons after their boots were hung up, the two shared ambassadorial roles and met at corporate events. Stransky was taken by the sharp contrast in the pillaging terror of Lomu on the field and his soft bashfulness off it.

“What a gentle soul he was, really quietly spoken, deep and caring in his approach, sympathetic. Not attributes you normally associate with a raging bull. When he ran, he snorted, he had this real aggressive look. To get to know him was great. As a human being, the world is a lesser place without him. He was a good rugby man, a good human being.”

Jonah got a fax, signed by you, telling him you were gonig to turn him inside out and make a fool of him.

A year after being poleaxed by Lomu in Johannesburg, Richard Wallace played for Ireland against a World XV at Lansdowne Road. He was having a drink with Lomu’s great friend and big brother figure, Eric Rush, when the most cringeworthy ruse was revealed to him.

“Eric said to me, ‘I’ve got to ask you a question. Did you write Jonah a fax?’,” Wallace remembers.

“’What do you mean?’

“’Did you send him a message before we played you in the World Cup?’

“’Jesus, no I didn’t, what are you talking about?’

“’He got this fax sent from the Sunnyside Hotel in Joburg, signed by you, telling him how you were going to turn him inside out, upside down and make a fool of him.’

“I said to Eric, ‘please, whatever you do, go back to New Zealand and tell anybody you know I did not do that!’ In fairness, he did and Jonah put it in his autobiography.

“There’s no evidence, but you’ve got to assume it was someone in the New Zealand management who did it, trying to eke out an edge. Being on the receiving end of a wind-up wasn’t what you might have hoped for…”

Joubert would come up against Lomu only once more, a year after the final. He scored a try as South Africa lost 15-11 in Christchurch.

“In 1995 Jonah was 19, I was 31. I said to myself, thank goodness I’m coming to the end of my career, I don’t have to play this guy at his peak. When an ‘oke’ like that comes at you full-speed… I had a few goes at him post-95 but he either ran over me or around me, so I know how Mike Catt feels.

“His impact was huge. The average age in teams back then was probably 28-30. Here he comes at 19. He draws that young generation into the World Cup. He attracted youth to watch rugby and contributed a lot to the growth of the game. Everybody said, ‘I want to be like Jonah’.

“Ask any rugby player now, young or old, they will know who Jonah was. His power and speed, and also his character. He had a soft heart off the field, people saw the good man he was. On it, he was a demolition man.”

Lomu was not unstoppable. South Africa proved it. That does nothing to denigrate his immense contribution to rugby. A game-changer for a sport clumsily entering professionalism. He had a video game named after him. He was in adverts for Pizza Hut and McDonald’s. He had offers from rugby league and American football that would have dwarfed the wages on offer in union. He never took them up.

“We are thankful to have been in an era of the game when you had a character like him creating such a massive impact and being part of taking our sport forward,” Underwood says. “The tragic thing is he’s not around with us to be celebrated again.”

Lomu died of a heart attack in November 2015, linked to the ongoing kidney problems for which he was receiving dialysis. As another World Cup approaches, we applaud his achievements and gawp at his clips all over again. His game is as marvellous now as it was nearly three decades earlier.

He ignited such massive interest in rugby everywhere he went. A beacon for young and old, he cleaved a path so many have trodden. One can only really be a trailblazer if others follow in their path. The plethora of gigantic backs in the modern game, from Nemani Nadolo and Alesana Tuilagi to George North and Duhan van der Merwe, let alone the countless men and women who cite Lomu as their inspiration for picking up a ball, or the young Pasifika population who saw him as an idol and a hero to emulate, stands testament to his lasting footprint. That’s his legacy; indelible and indisputable. The great sorrow is that he is no longer here to be honoured in life.

Every Christmas Eve, once the socks have been fished from their place and planted in the hearth, Joiner pours himself a dram.

“My daughters are 16 and 19 now and Jonah’s socks have been used as Christmas stockings pretty much every year,” he says. “That’s a wee moment to raise a glass to someone who was a very special rugby player.”

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free