The shortened 2020 season for the All Blacks ended as one of the more disappointing in recent times. Not only were the results historically bad, the style of rugby didn’t reach any great heights as the squad tried to build under the direction of new head coach Ian Foster and his assistants.

While Foster has been in the All Black environment for a long time, his assistants are fresh to the job.

Most of the criticism or praise for any result is aimed at the head honcho, but many of the assistants will be key decision-makers for their portfolios and have a heavy influence on outcomes.

Those new assistants have ideas and strategies for where they want to take the side, so it is expected that the All Blacks’ style of play would change even though Ian Foster has been there a long time.

In 2020, we saw pattern and scheme changes as the side adapted throughout the season. After one showing in Wellington, the side ditched their 2019 pattern in favour of something that would better suit first five Richie Mo’unga. After losing to Argentina with a laborious carry game in Sydney, they increased the number of attacking kicks to add more variation.

These changes are more identifiable as they are cut and dry areas that are programmable by coaching staff. It doesn’t matter so much who is in the team, the players can be arranged to play in a formation by a set plan that doesn’t deviate.

Less noticeable are changes that occur over time in areas of the game that are less controllable. Counter-attacks off kick returns and turnover ball are driven more by philosophies and individual skillsets than hard concrete plans.

It is free-flowing rugby that develops as the players create it. It isn’t controllable to the degree that a phase play pattern or launch play is, but is typically guided by common understanding, policies and players’ skillsets meshed together.

Most of the criticism or praise for any result is aimed at the head honcho, but many of the assistants will be key decision-makers for their portfolios and have a heavy influence on outcomes.

The players need a framework to operate in but only they can find the right answers guided by policies. If a turnover is won, the ball is immediately spread to the edge. If a kick is received in a midfield zone, the opposite edge is hit within two phases.

Time and energy needs to be spent sharpening those tools and building chemistry and a shared understanding between teammates to fully capitalise on those windows.

The All Blacks found it more difficult in 2020 to pull off the free-flowing movements that they have done in the past, laden with silky passing and keeping the ball alive through offloads.

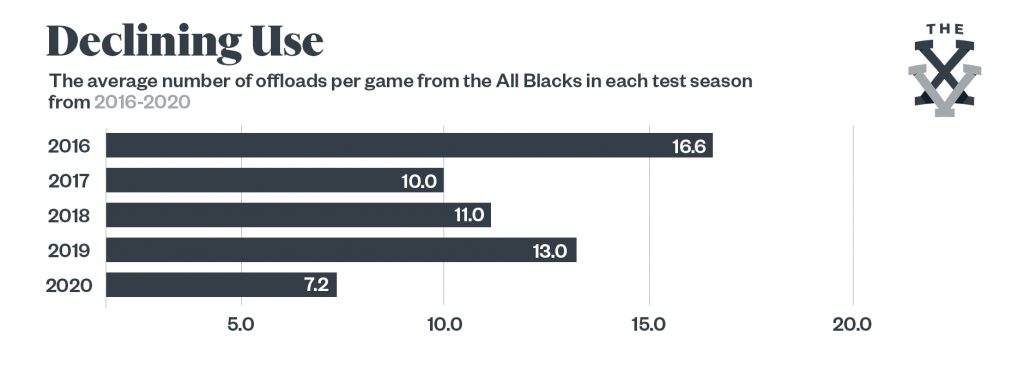

The number of offloads per game the All Blacks make is decreasing, with the first year under Ian Foster becoming an exaggerated outlier over the last five years.

From an average of nearly 17 per game in 2016 the All Blacks managed just over seven last year, a decline of over fifty per cent.

The World Cup year in 2019 indicated the numbers were heading up with an average of 13 per game, but this figure was inflated by lesser competition in the pool stages in Japan with games against Canada and Namibia.

Removing those two games, the All Blacks averaged 9.0 offloads per game, continuing the longer term downward trend.

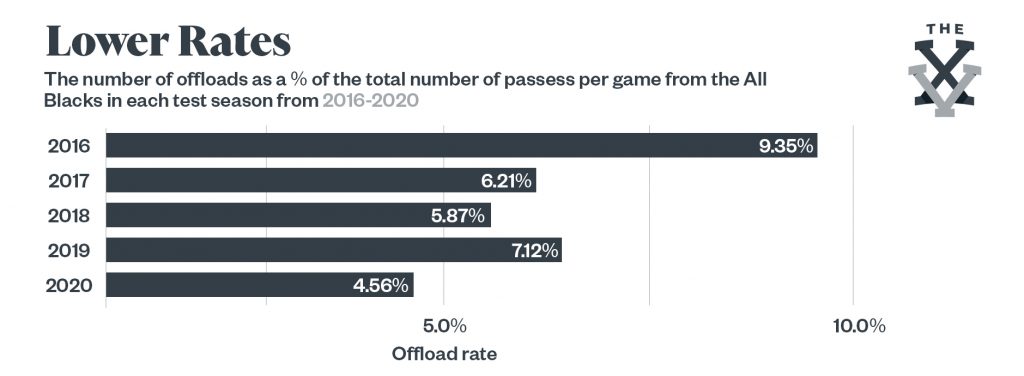

As a percentage of total passes, the number of offloads in 2020 was less than five per cent.

The All Blacks are promoting the ball less, keeping the ball in hand and going to ground more than ever.

Correlation doesn’t always equal causation, but when the offload rate was above seven per cent during this period, the All Blacks won 92 per cent of their matches. When the rate was less than five per cent, the win rate dropped to 58 per cent.

It makes sense that when defences are strong, offloads are tougher to make and as a result, fewer attacking opportunities surface.

Whilst the answer to getting back to a dominant win rate isn’t as simple as ‘offload more’, there should be a desire to find out why this is happening and whether opportunities to offload exist that aren’t being taken.

The 2016 All Blacks were a fantastically strong counter-attacking unit and averaged over 40 points a game, so it is no surprise to see their offloading numbers were so high.

The ascension of Beauden Barrett into the starting line-up combined with the likes of Ben Smith and Israel Dagg in the backfield offered multiple threats in the kick return game. All three players were elusive, fast, broke tackles and looked to link up and keep the ball alive once stopped. They all had rounded skillsets that could be used together and had spent years in the team forming combinations.

Against Wales in the third test of the June series, the kick return game around these three players tore the Welsh to pieces in a 46-6 win. Offloads often turned movements into long line breaks. If they did not score directly from the counter-attack, they often would shortly after as a scrambling defence offered opportunities.

The All Blacks had the attacking mastermind of Wayne Smith on the coaching staff, who is known as an evangelist for keeping the ball alive and capitalising on free-flowing attack. 2016 was the last full calendar year he coached the side, having retired in 2017 following The Rugby Championship.

In 2020, the All Blacks’ preference for structured play and dying with the ball was more present than ever, seemingly without the ethos of which Smith was a proponent.

There could be a vast array of reasons for this strategic change, aside from the loss of Smith’s influence in the coaching brain trust. The 2020 international season was disrupted from the beginning with entirely new challenges to overcome. The limited preparation time meant the team could not implement everything that they desired and kept things simple.

It’s true that the defences in international rugby are becoming more organised, more powerful and harder to break down, but there could be other factors at play in this lower offload rate. A largely new squad in 2020 meant rebuilding chemistry between untried combinations.

One thing that became clear was the lack of chemistry between players that had not played together much before.

For example, young Blues wing Caleb Clarke’s only game time with Beauden Barrett had come in that season’s inaugural Super Rugby Aotearoa campaign when the former Hurricane linked up with his new club.

With Barrett at fullback, the pair were intricately linked in the All Blacks back three and would combine frequently inside and outside one another in the backfield or on set-piece launches but they never found the chemistry where they could read each other’s game.

Barrett often saw opportunities to run support lines outside Clarke, but the run-first wing didn’t look or anticipate an offload to his fullback.

In the final test of the season against Argentina, this was visible on multiple occasions. Despite the All Blacks winning by a comfortable margin of 38-0, it was moments like these that left the impression that things weren’t clicking.

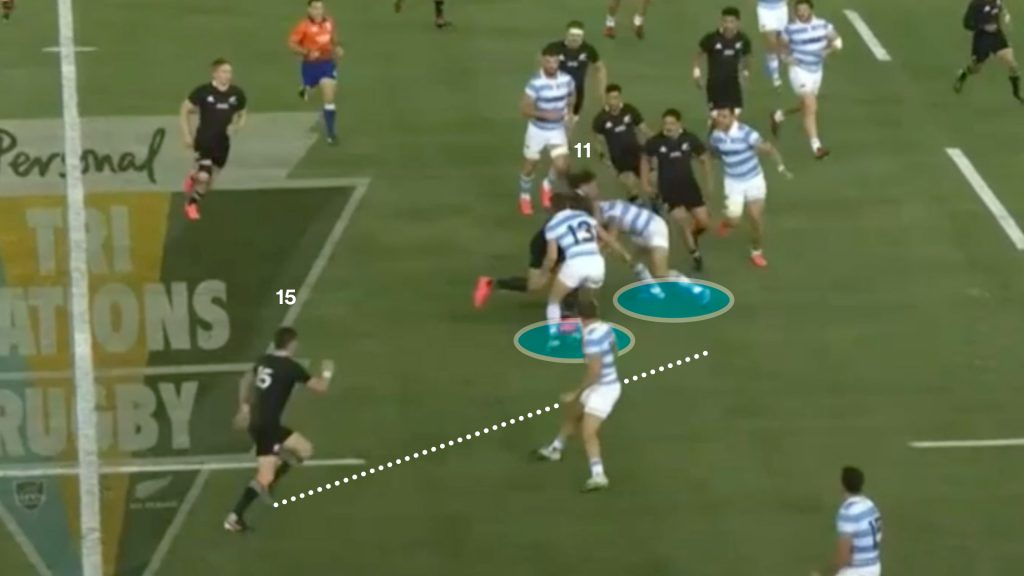

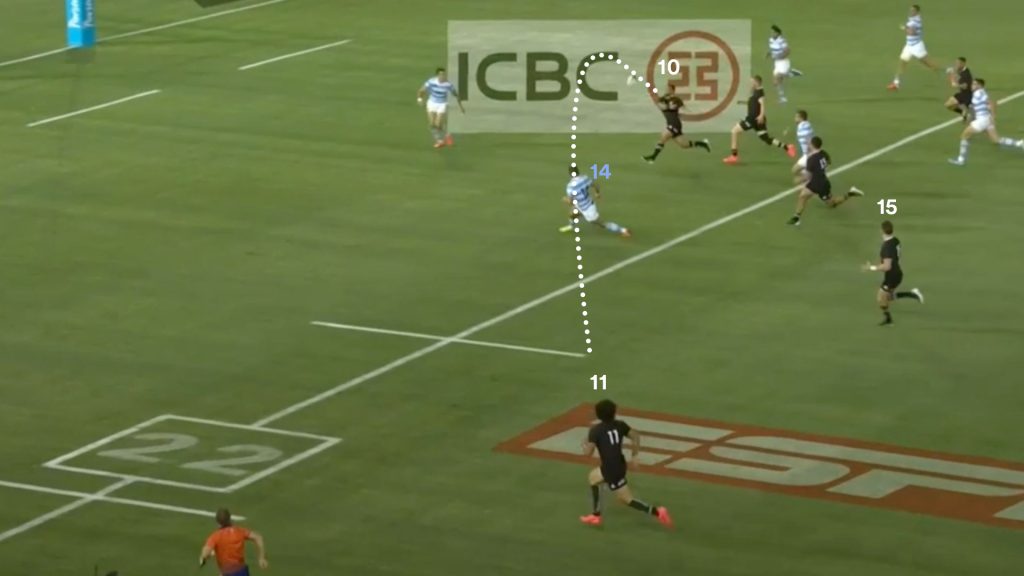

A line break midway through the first half by Richie Mo’unga went to waste as the Blues’ pair couldn’t connect to finish off the opportunity.

After receiving the long pass from Mo’unga, Clarke had the opportunity to fix the nearest defender Santiago Cordero (14) and play Barrett wrapping around the outside.

The pressure would then be on the next Argentine cover defender to catch Barrett, which would be a near-impossible task from that situation.

Instead, Clarke backs himself to beat Cordero one-on-one on the outside and takes the same space that Barrett is after, running his fullback out of play as a supporting option.

It’s not necessarily a bad option given Clarke’s power and size, but it illustrates that the two are not singing from the same song sheet and aren’t familiar with what each other are seeing.

It is what you would expect from two players that have only played together a handful of times.

Unfortunately for Clarke, despite breaking the tackle of Cordero, he trips over and hits the touchline in the process of getting the ball over the chalk and the All Blacks don’t score. Argentina get a penalty from the ensuing line out and escape without conceding any points.

Had the two had been on the same page and hunted as a pair, Barrett may have gone over untouched with a simple draw and pass or offload in the contact of Cordero.

It is the type of moment that typified the All Blacks play in 2020 – missing the polish and execution to finish promising lead-up work, leading to frustrating periods of play.

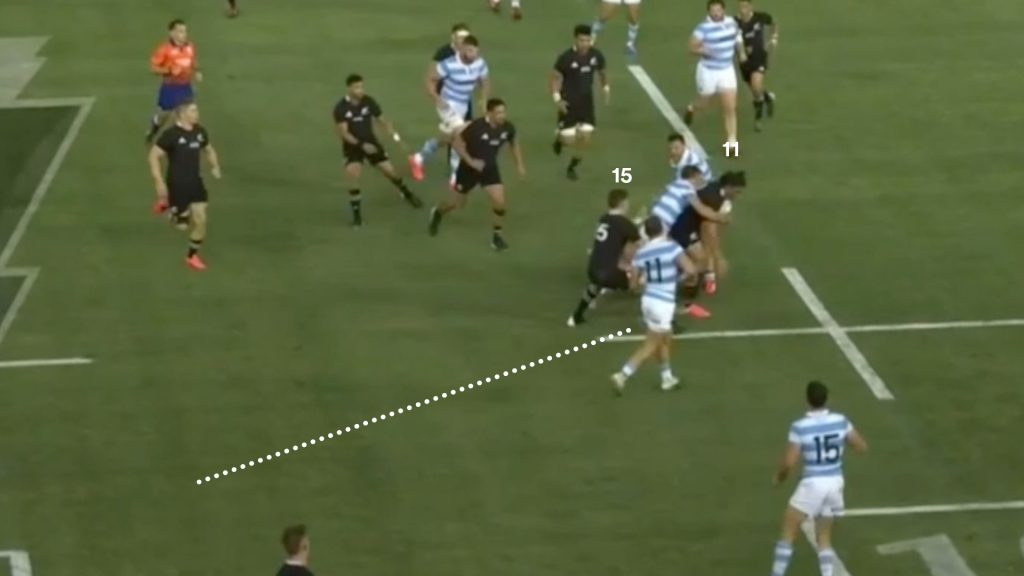

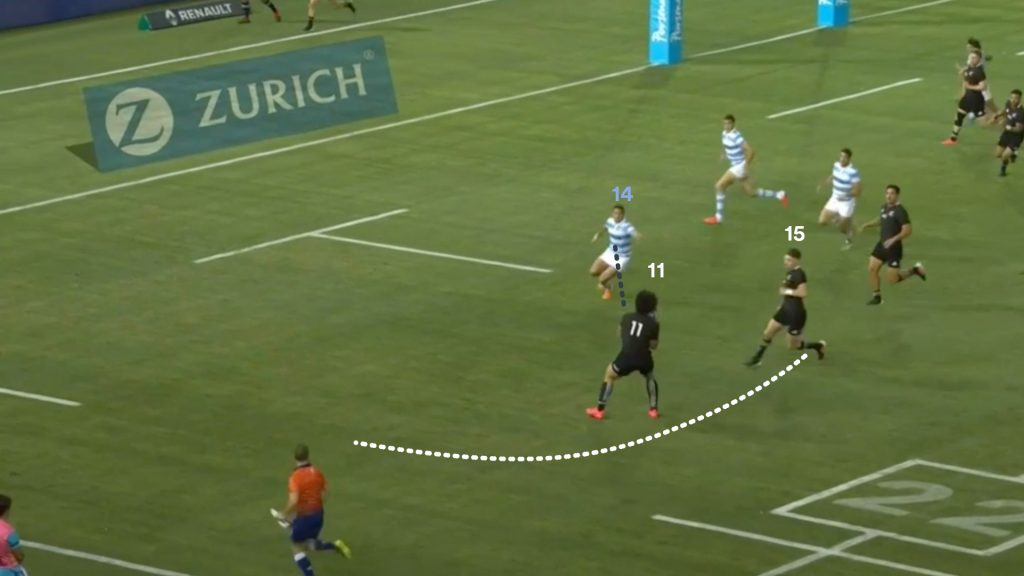

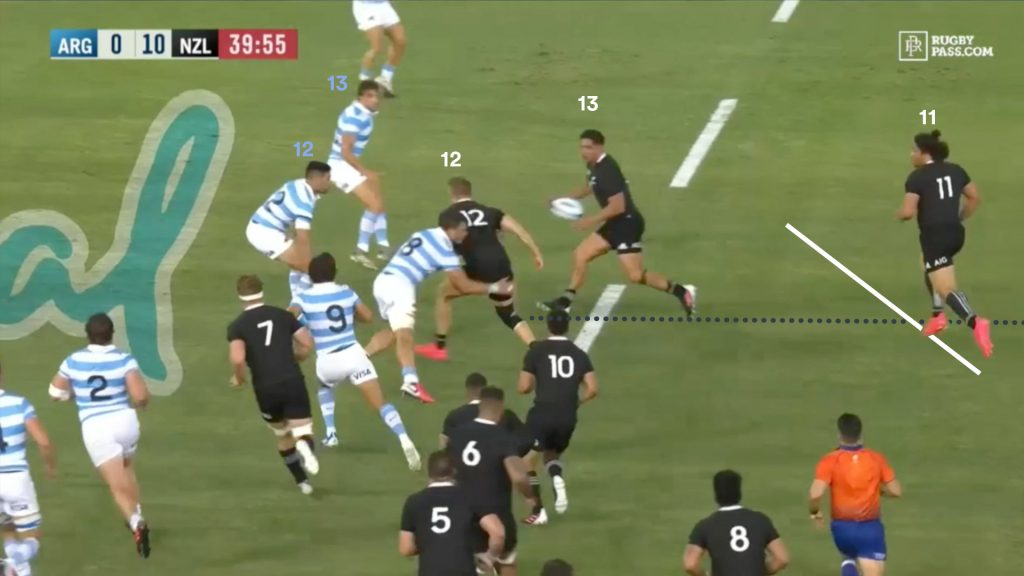

Right on the stroke of halftime, we see this dynamic between the two play out again on a starter play where Clarke injects into the back line off his left wing. The All Blacks play Clarke out the back of a midfield block line by Anton Lienert-Brown (13) to try to get Clarke free around the edge.

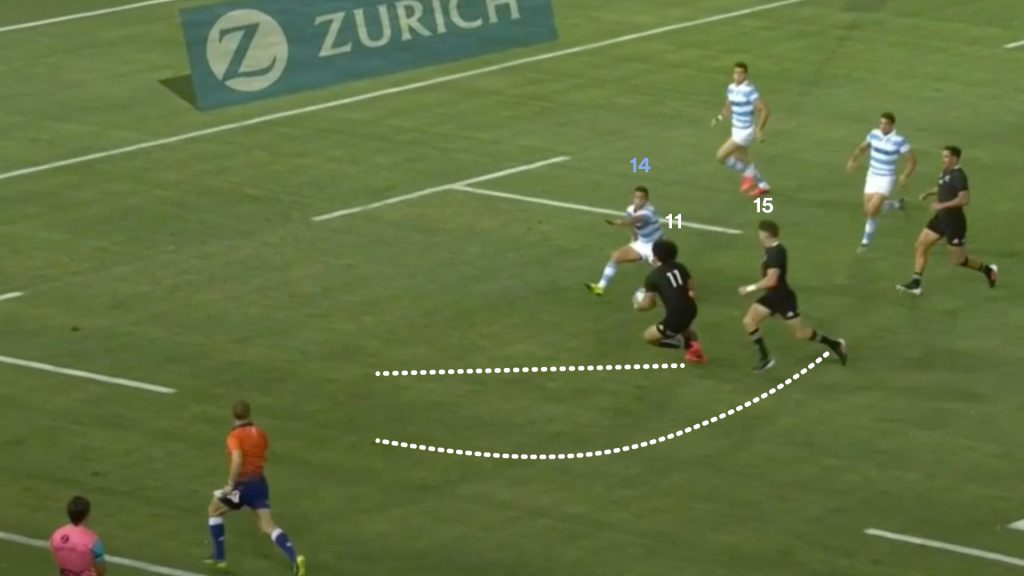

Clarke punctures the Argentinian midfield with strong carry, leaving both defenders on the ground around his ankles momentarily before they both fall off. The low tackles leave Clarke’s arms free, available to promote the ball.

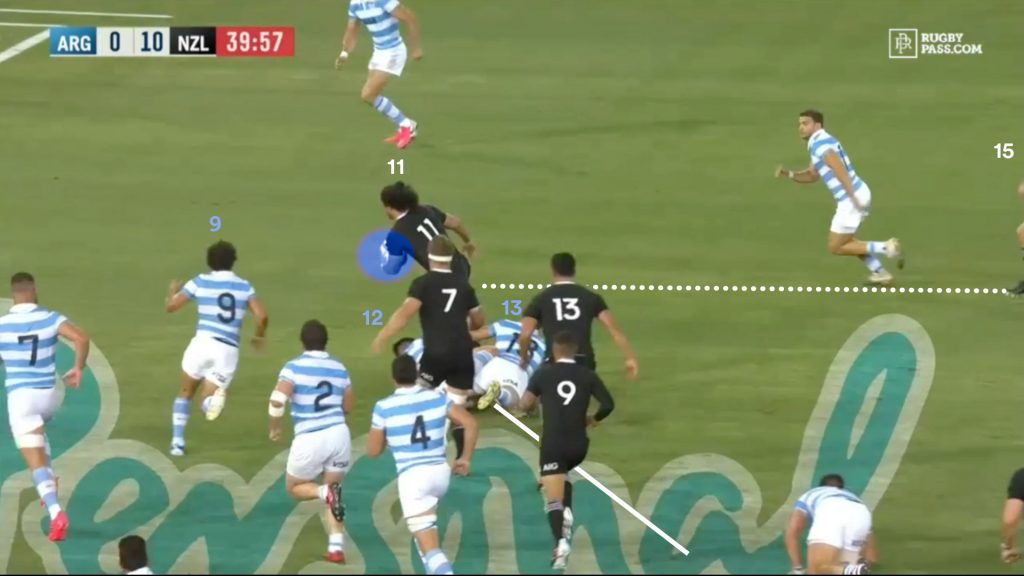

Sensing an opportunity to inject outside Clarke, Barrett flies up on the outside looking for the pass off Clarke’s hip.

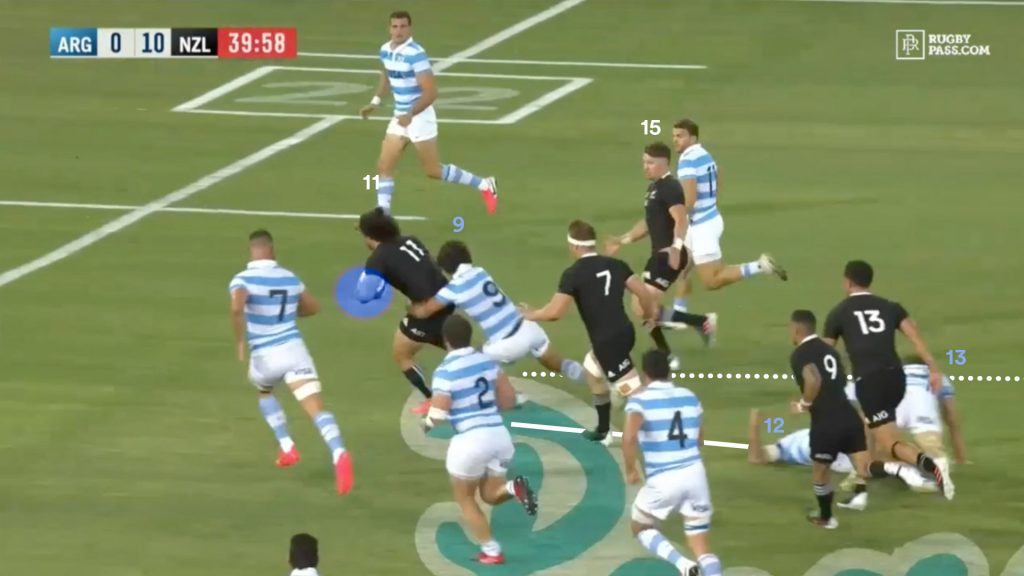

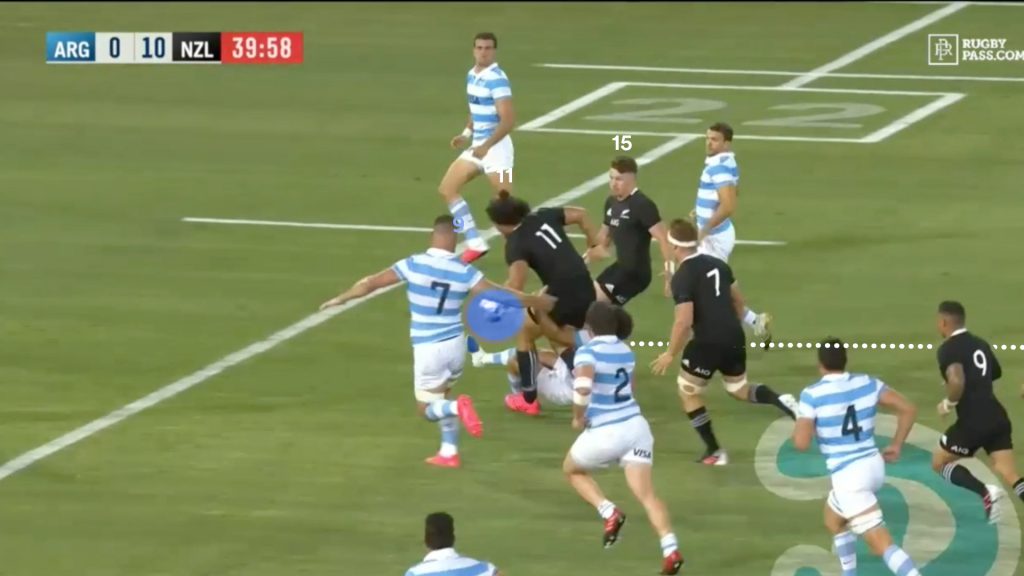

The Argentinian halfback is forced to make the cover tackle on Clarke, a low side-on chop tackle leaving the ball-carrying arm free once again. Barrett (15) wants the pass but it isn’t forthcoming as Clarke tries to break the tackle and keep going.

Barrett, in the end, overran the play and Clarke died with the ball going to ground in the tackle.

For fullback Barrett, these missed opportunities are the difference between having a quiet game and completely breaking the game open with the type of plays we are used to seeing from one of the world’s best players.

He often put himself in the right positions but a lack of chemistry meant he wasn’t getting into the open field. He finished the four games in the Rugby Championship over in Australia with zero line breaks and one tackle bust, a world away from the Barrett of 2016 and 2017.

Against the Springboks in 2016, the All Blacks struck from a turnover when Liam Squire found Barrett on a support line with a perfect offload. The anticipation and timing from both players was immaculate.

This type of play doesn’t happen without an emphasis on counter-attacking rugby, learned tendencies between players and a license to promote the ball as part of an overall framework that every player is aware of.

It really seems that this has become a low priority for the All Blacks under Foster and his staff. This can be illustrated by how the All Blacks handled an ideal counter-attacking opportunity early in the second half of the last test against Argentina.

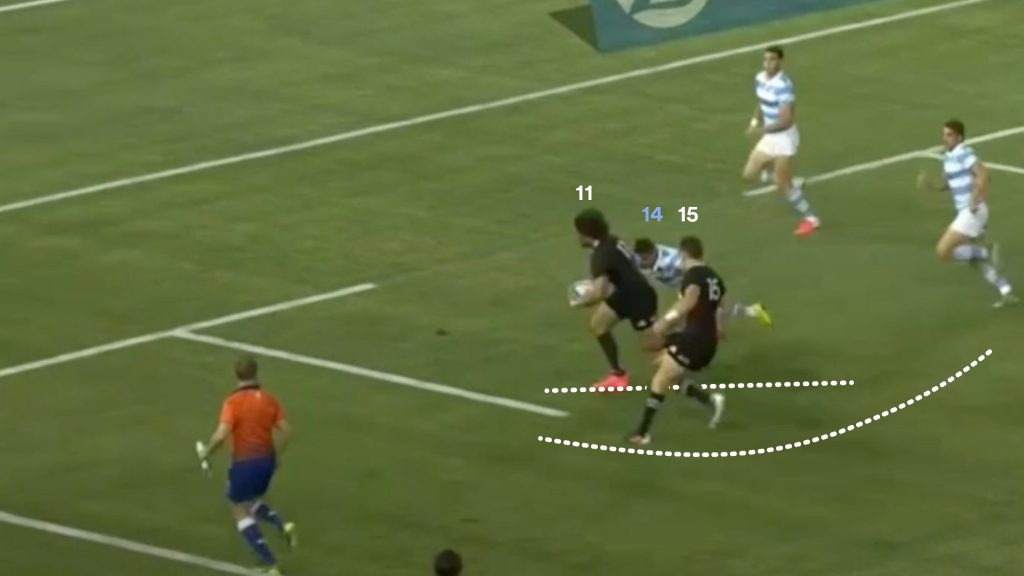

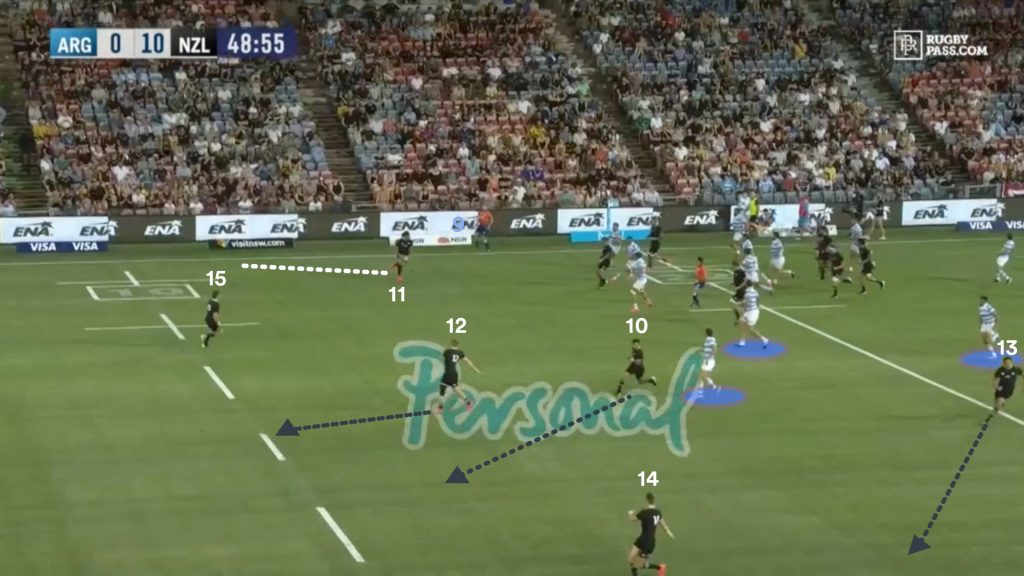

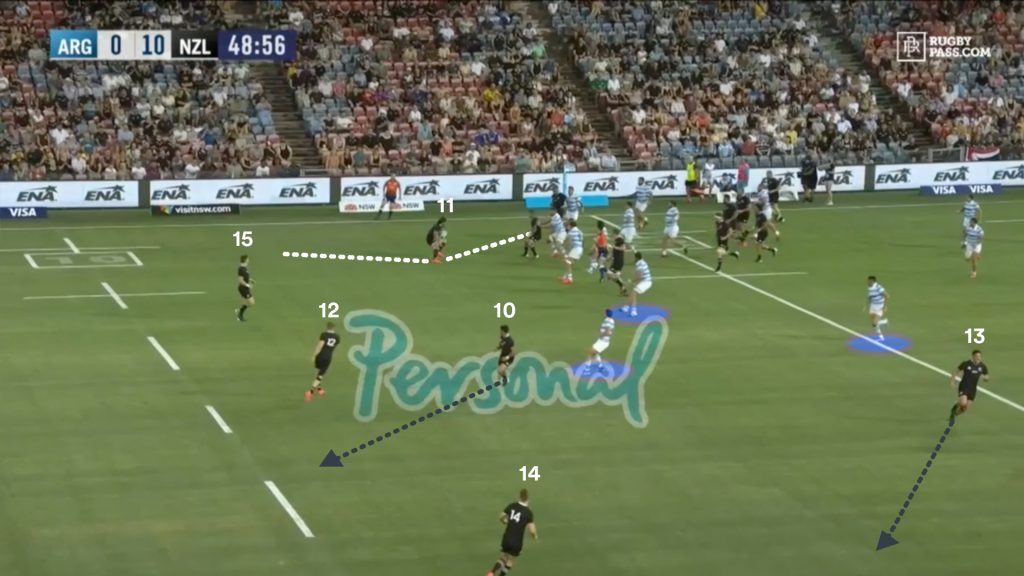

An exit box kick fails to find touch and Clarke is gifted with the opportunity to bring it back on a kick return inside the Pumas’ half. With the Pumas congested on his side, the space is on the far side to counter-attack.

We see the All Blacks’ backs anticipate a counter-attack to the far side, with all of them working hard to spread the field and create numbers to use across the full width.

Richie Mo’unga (10) and Anton Lienert-Brown (13) aren’t even looking at Clarke with their backs turned, understanding the opportunity requires them to get back into a position quickly to be involved when the ball swings to the right side.

However, Clarke doesn’t link with the next man Barrett and cuts back to set-up play around the 22.

This decision by Clarke doesn’t completely end the counter-attacking opportunity. During the next phase, the defence is still in transition so the far side can still be targetted where defensive numbers are fragile. Aaron Smith can release the backs by linking with Barrett behind the forwards in the second level.

However, the All Blacks play a forward runner direct off the halfback instead of releasing the backs in behind.

The second phase is another forward carry off 9 into the teeth of the Argentinian defence, which has been reinforced with solid numbers at this point.

The third phase is a switch back to the short side, and ends with another forward carry after a tip pass from Sam Cane. The movement eventually ends with a knock on from a flat pass from Aaron Smith, metres from the line after many phases.

There is no intent throughout the entire passage to use the transition play to attack the Pumas where they are weakest, on the far side edge. There is a clear directive to run over the Pumas down main street, using power runners off 9 repeatedly. It is slow, laborious rugby, based on power over skill and speed.

We saw the All Blacks move towards this style of confrontational play in the 27-7 demolition of the Wallabies at Eden Park, before it came unstuck in the first-ever loss to the Pumas in Sydney. In the last test of the year, it still persisted in a 38-0 win that was anything but clinical.

Former All Blacks assistant Wayne Smith, when interviewed recently on the state of New Zealand Rugby, called for more efficiency in attack instead of playing ‘robotic’ phases through pods.

“One of the things I’ve noticed since I got back from Kobe about five weeks ago is everyone’s playing pods, so they’ll have three forwards off the No 9, for example, but we seem to have become kind of robotic, going through the phases,” Wayne Smith told the panel on The Breakdown.

Smith said he believed most tries come within three or four phases of a possession, leading to questions around why New Zealand has adopted such a rigid game around long-possession phases.

“It’d be interesting to know how, many phases does it take to score a try? I’m picking it’s probably three or four phases.

Attempting to play long phase counts to wear down an opposition is fraught with execution risk, as the All Blacks found last year.

“Probably 75 per cent of your tries come from those three or four phases. I’d like to see us be a bit more efficient and effective off those plays.”

Particularly with the way the breakdown is going, the risk of losing your own ball while in possession has never been higher as the crackdown on poor clean outs has escalated. Attempting to play long phase counts to wear down an opposition is fraught with execution risk, as the All Blacks found last year.

Re-booting the All Blacks counter-attacking game and finding a way to re-utilise the offload could be the way to revive what has become a concern with the attacking prowess of New Zealand rugby in 2021.

The All Blacks should get the benefit of the doubt for their form given the circumstances that unfolded last year, which leaves much room for improvement heading into year two under Ian Foster and his staff.

A year under the belt of a number of rookies should hold them in good stead to build more fluent combinations as the coaches look to mould a squad capable of winning the World Cup in France.

Hopefully they learnt that the identity of the team as a forward-orientated, power-based unit can only go so far. When pitted up against those top teams with a strong defence who can’t be bullied into submission, life can be difficult.

The strength of the New Zealand’s rugby, and by extension the All Blacks, of high tempo, skill-based rugby, should not be lost in the obsessive age of brute power and kick chase.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free